Belonging: A Place at the Table (Part 2) (OpEd Piece)

/“One nation,

under God…

with liberty and justice

for all.”

A young, bright-eyed Black child, his little hand on his heart, recites the Pledge of Allegiance. His earnestness and enthusiasm make me cry. It brings me back to my first grade classroom where I first learned and so earnestly recited the pledge at the beginning of each school day. I felt so proud then, in my innocence, just as this innocent little boy is as he proudly grins at the adults in the wings, assuring him he has done a good job.

Innocence. Hopeful possibility. Being part of “the greatest country in the world,” a country different from all others in its ideals. These are the values that many of us were raised on. Yet, here we are at a pivotal moment in our country’s history. A country that is seemingly falling apart at the seams. A nation imploding.

How did we get to be in such a place?

I am not a social scientist or political analyst, so my perception may be more limited than I am even aware of. I am a social worker, a teacher, and a person of faith. I am a therapist who specializes in family of origin work, who has worked with thousands of people in pain for almost 40 years. I have learned a lot from the many people who have reached out for help.

From my teachers, clients, and my own life experience, I have come to see that when we know our family history and accept it without judgment, we can appreciate how it has affected us and let go of what no longer serves us. This frees us to create our own path in life with a more open heart. I have also found that when we don’t, or can’t look at where and whom we’ve come from, we often unconsciously become caught up in a legacy of patterns, behaviors, and beliefs that can be life-limiting, robbing us of access to parts of our soul. We may even passionately defend and justify these beliefs and behaviors because we are disconnected from the deeper dynamics that formed them.

This is the lens through which I am viewing our nation right now.

Denial: Family and Community

Denial enables us to go on with our lives

as if nothing of import is happening.

In psychology, we refer to “Denial”—an inability to see reality for what is because it is just too horrifying or overwhelming to do so. It is a refusal to appreciate the full extent or impact of the pain and devastation of an event. Denial is an essential part of the protective nature of the mind to help us survive in situations that engender overwhelming fear or guilt or shame; situations in which we feel helpless to do something to change it. Denial enables us to go on with our lives as if nothing of import is happening.

In families where there is unacknowledged abuse or severe neglect, some go so far as to blame the victim for their suffering, demonizing acting out behaviors rather than facing the root causes. Denial causes us to blame the victim because it is easier than looking at what’s going on within the family and community while excusing us from having to take action. The victim, in turn, almost always internalizes this judgment and blames her or himself.

Denial: A Nation

Denial of the extent and impact of oppressiveness and violence can make us feel crazy when it happens in our own family. It is the elephant in the living room that everyone knows is there but pretends it’s not. On a national scale, this denial is devastating for a large number of people in our country.

I have come to believe that an important problem facing our nation is that there has been too little transparency about the countless vital and brutal aspects that make up our history. Facts are too often “forgotten” and/or ignored, like how the bodies of Native Peoples, Black people, immigrants of every shade of color were used and abused, never repaid by their oppressors for the injustices they suffered and sacrifices they made to build our nation. To this day, this history is not fully seen, acknowledged, or honored.

“The reason we get lost is because we are lost in the

darkness of ignorance, illusion and delusion.”

-Dr. Brenda Shoshanna, Phd, Zen Teacher

For hundreds of years, White Americans have lived in collective denial about the brutal details of our country’s history. Why? Because it is easier to choose to remain loyal to the beliefs and values we were raised with that keep the national “family” innocent of responsibility for change. Then, we put the blame on the victims. These denials sound like:

“Different is suspect and not to be trusted…”

“You get what you deserve…”

“‘Indians’ [Native peoples] live on reservations because they want to…”

“Black people are dangerous and lazy….”

“Immigrants from south of our border just want a handout.”

“You can achieve whatever you want if you are willing to work hard enough for it…”

And perhaps the most unconscious and insidious: White Supremacy—the deep-seated belief that White people are superior, and that “everyone else” should strive to be more like “us”; anyone who disagrees with the prevailing beliefs could be, and often are judged as “disloyal,“ “suspect,“ “un-American,“ and even “traitorous“ for standing, kneeling, or speaking up in recognition of oppression.

Every person has a story that puts context to his or her life, but we are often taught to measure the value of one’s life mostly by how much money one has accumulated and how much power one wields. White folks are often blind to the injustices that People of Color—especially Black folks—have endured. Instead, Black people are blamed for their present life circumstances, while the resilience that they have developed as a result of their endurance becomes minimized.

What Does Privilege Look Like?

One of the strongest narratives among White folks I know goes like this: “I’ve suffered, too. It hasn’t been easy, but look at where I am today.” While this path may certainly not have been “easy” or even without suffering, for many of these folks—myself included—we were fortunate to have had an adequate, safe place to sleep; enough food; access to education, and people we knew from school who helped us get a job. At those jobs, we had people who taught us the ropes, who believed in us, who encouraged us, and who supported us. We had people who taught us a “can-do” and “you deserve better” attitude.

But most importantly, even if we didn’t have all or even some of these things, one thing we didn’t have to worry about was being judged by the color of our skin as we walked to school, to the grocery store, or to places of worship—and that is what White Privilege looks like. It has prevailed for centuries, and it has taken more and more mental gymnastics to keep from our awareness that our self-asserted “greatest country in the world“ was built on a foundation of sand beneath which we can find thousands of brutalized bodies of murdered Native people and kidnapped Africans.

The process of Denial of this reality cuts us off from parts of our soul. Many will say, “But what has that to do with me?” or “That was a long time ago.” We don’t want to see how our beginnings as a country are still affecting our souls—how for the past 135+ years, we have tried to keep the caste system going through denial, through laws that privilege Whiteness and keep the rich and powerful immune from the vagaries of life. For all its wealth and power in the world, the soul of our country has been decaying from within as we continue to cling to denial about what has really been going on in the shadows.

The Tipping Point: A Renewed Awakening

So, what is the tipping point?

Over the past nine months, we appear to have experienced yet another tipping point, or perhaps an opportunity for a renewed awakening in our collective national consciousness. With the pandemic, life as we knew it has come to a screeching halt. While it has had many daunting and devastating consequences to our health and well-being—not to mention in particular, for those most vulnerable and marginalized in our country—it has also given many of us the gift of time to slow down and see our lives from a different perspective.

Many of those with the luxury of a secure home and income had begun to reassess what is really important—family, time, rest, nature, faith. Then, with the brutal public execution of George Floyd, on the heels of the killing of Breonna Taylor, our eyes were opened—some of us for the first time, for others, yet again—to what Black Americans have been trying to tell us for decades: that Black people have continued to be marginalized and brutalized by systems that aim to keep them in their place at the bottom of the social ladder.

It is crucial to pause and acknowledge that what is happening now is nothing new. The struggle has spanned generations—from Mike Brown to Eric Garner, Tamir Rice to Philando Castile, Emmett Till, and many, many more before them. Social movements calling for racial equity and justice have been in existence for years. Writings like White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack date back to periods of awakening decades old. Yet, it is only now that many of us have begun to truly put in the work to address it.[1]

Looking Inward: A Personal Reflection

My own awakening to the systemic nature of racism has been a long arc. I grew up in a neighborhood that quickly changed from a mostly White, working-class community to a predominantly Black neighborhood. My youngest brother was the last White child in our Catholic school. I watched as our neighbors and friends all fled to “Whiter” towns. Later, I would begin my teaching career in an all-Black Catholic elementary school, followed by work at an urban community health center. I’ve lived in a community that boasts over 30 languages in the school district, and where many of our friends were originally from Asia, Africa, and South America.

Despite these rich experiences, my Privilege only became apparent to me during my participation in a professional organization that challenged us to include social justice issues in our work with families. At our annual conferences, we participated in racial identity support groups, as well as a White Domination and Privilege group. To be honest, I was mostly unable to identify how all of this related to me, given my background. After all, wasn’t I married to a person of color? We didn’t have these issues between us!

Or so I thought.

A conversation between myself and my husband opened my eyes to what was right in front of me—that he was constantly aware of, and suffered, anxiety about how his skin color might be judged by White extended family members. Since that defining conversation, I have made it a personal priority to be mindful of the power differential between myself and whoever I am with—in my personal life and especially as a teacher and therapist. I learned—sometimes painfully—that my good intentions are not so important as the impact of my behavior, beliefs, and language on my friends and colleagues of color.

Then, I watched 13th, a documentary about the justice system in the United States.[2] The film presents a horrifying, sobering history lesson about the deliberately planned, strategic laws and policies that sent Black men and boys to prison from 1865 to the present day—first to bolster the Southern economy after the end of slavery, and presently, to keep the privatized prison system economically profitable.

I could no longer remain blind to what I now understand to be systemic racism.

A Flawed System

Systemic racism refers to systems that are deliberately put in place to perpetuate keeping power in the hands of White people. It is about chattel slavery that separated families and used Black people to create a vibrant economy. It is about Jim Crow laws and housing policies that continue to disenfranchise Black people. It is about policies that determine where you live, the quality of your education, how you acquire wealth, the quality of and access to healthcare, the level of policing in your community, who goes to jail and who doesn’t for the same crime, and who gets access to voting.[3] Laws and policies are what distinguish systemic racism from prejudice and discrimination. And while it is difficult for some White folks to see it, we have implicitly maintained these systems through denial.

Photo credit: Getty Images/Gary Waters

Now, we have yet another opportunity to make a choice. We can choose to remain blind to the inequities in the systems that continue to maintain White Supremacy and keep people of color, especially Black people, from participating freely and fully in our country. Or, we can choose to open our eyes to a history of planned dehumanization followed by disempowering laws and policies that keep a symbolic foot on the necks of Black people.

Take the example of the fraud and greed of the school superintendent and the business administrator of a Long Island school district, where White leaders stole more than 15 million dollars from the children entrusted to them. The superintendent spent three years in prison for grand larceny, but he has been allowed to continue to collect his almost $175,000 annual pension.[4]

On the other extreme, we have Fair Wayne Bryant, a Black man who was recently refused leniency by the Louisiana Supreme Court while still serving a life sentence for attempting to steal three hedge trimmers 20 years ago.[5] Thanks to a Jim Crow law enacted in the South at a time when free labor was needed to keep the economy going after the Emancipation Proclamation “freed” slaves, the court felt justified in keeping this 60-year-old man in prison for stealing garden tools. And yet, while we may shake our heads about the terrible unfairness of these cases, it is still far too easy to fall back into denial about the far-reaching implications these inequities exemplify in our country.

Putting in the Work: A Change of Heart

In today’s present crisis of chaos and conflict, it is ever more urgent that we work harder to see and acknowledge those who came before us, neither excusing nor judging them, but rather opening our hearts to the pain and challenges of their fate. Only then can we become free of “invisible loyalties” that bind us, blind us, and block our path to a new reality that will create a peaceful heart.[6] Only then can we extend our hearts to others.

This is not so easy a choice as it may seem. This change of heart requires our commitment to playing our part in creating a more just society. It requires an honest look at the many unconscious biases which we continue to perpetuate, biases that have been passed down for generations.

“Act justly, love mercy and walk humbly with your God”

- Micah 6:8.

For me, it means challenging my implicit biases—we all have them—about people who don’t look like me, love like me, or worship like me. It means suffering the “guilt” of going against longstanding family and cultural beliefs. It means respectfully standing up to racism when I see it—even, and perhaps especially with people I love and admire. It means acknowledging racial or other biases in my own attitudes when they surface. It means learning about the untold stories in the history of Black America. It means learning to speak to people of color without putting them in the position of consoling me for my guilty feelings, of excusing me for my missteps, or of minimizing the hurt I cause for fear of alienating me.[1]

Moving Forward: Leading Through Compassion

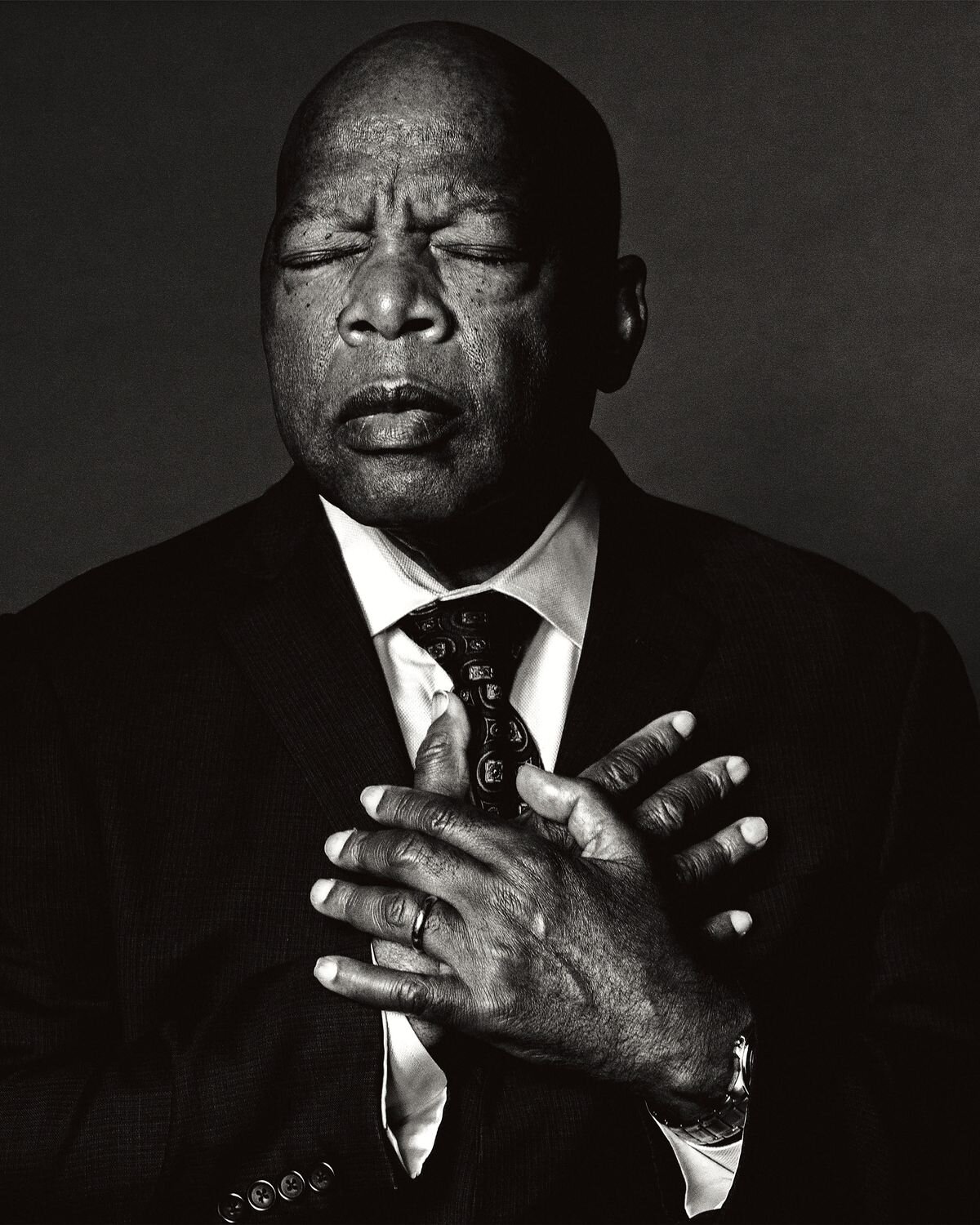

Many Black leaders and allies in the movement for justice and equity for all Americans have been some of the most compassionate spokespersons about this challenge, setting the stage for the change of heart that can happen in this country.[7] Leaders, like the late Representative John Lewis, who have put aside the burden of rage in the face of their painful, unjust treatment in this country are imploring White America to look more deeply at how the implicit evil of Racism has been bred into our culture, and how it continues to undermine our best efforts to grow and heal as a country. I am moved beyond words by the generosity of spirit this position exemplifies: no blame, no shame. Just an invitation to see and acknowledge Racism as the unifying enemy, and an evolved understanding that change can only happen if there is a willingness to work together.

via New York Magazine

These leaders remind us that we are Brothers and Sisters, part of a human family bigger than any tribe or race. Perhaps, if we can get past the invisible loyalty to our nation’s white-washed version of history, we can begin to understand the connection between the experience of our non-White Brothers and Sisters and what they are fighting for now. We can open up our hearts and become allies, acknowledging past wrong-doings without defensiveness, and validate the right for all to belong and have a valued place at the table.

“When I find my home, my soul is at rest,

When I find my place, Peace.”

- Zen teaching

Whether we are addressing the anger and alienation in individual families or the real possible end of our culture in the face of racism and hatred, we know that no substantive change will happen if we continue to keep our hearts locked up within the confines of our own implicit biases. White America needs to take up this vital work so that by walking together, we can find a path of healing that will lead to lasting reconciliation. It is not easy, but our children and grandchildren through the generations will thank us for our courage in doing so.

The Lessons From the Journey collection continues in 2021.

© Whatismyhealth

Special thanks to our resources:

DiAngelo, Robin. (2018). White Fragility: Why It's So Hard For White People To Talk About Racism

DuVernay, Ava, director. 13th. 2016. YouTube, www.youtube.com/watch?v=krfcq5pF8u8.

https://www.businessinsider.com/us-systemic-racism-in-charts-graphs-data-2020-6

https://www.vanityfair.com/hollywood/2019/09/hugh-jackman-movie-bad-education-scandal

https://www.dramandakemp.com/racial-justice-from-the-heart-2

Additional resources:

http://www.antiracismdaily.com/?utm_campaign=subscribe--&utm_medium=email&utm_source=newsletter

https://www.tolerance.org/magazine/fall-2018/what-is-white-privilege-really

Understanding our attachment styles can help us bypass destructive strategies and find a more authentic connection.