One in the Field: An Exploration

/“Out beyond idea of wrongdoing and right-doing,

there is a field. I will meet you there.

When the soul lies down in that grass,

the world is too full to talk about.

Ideas, language, even the phrase ‘each other’

doesn’t make any sense.”

- Rumi

You, or Me.

“Right,“ or “Wrong.”

“Good,” or “Bad.”

“Insider,” or “Outsider.”

All are binary examples, a way of dividing our world into either/or, a way of thinking that separates us by making judgments. This is called dualistic thinking.

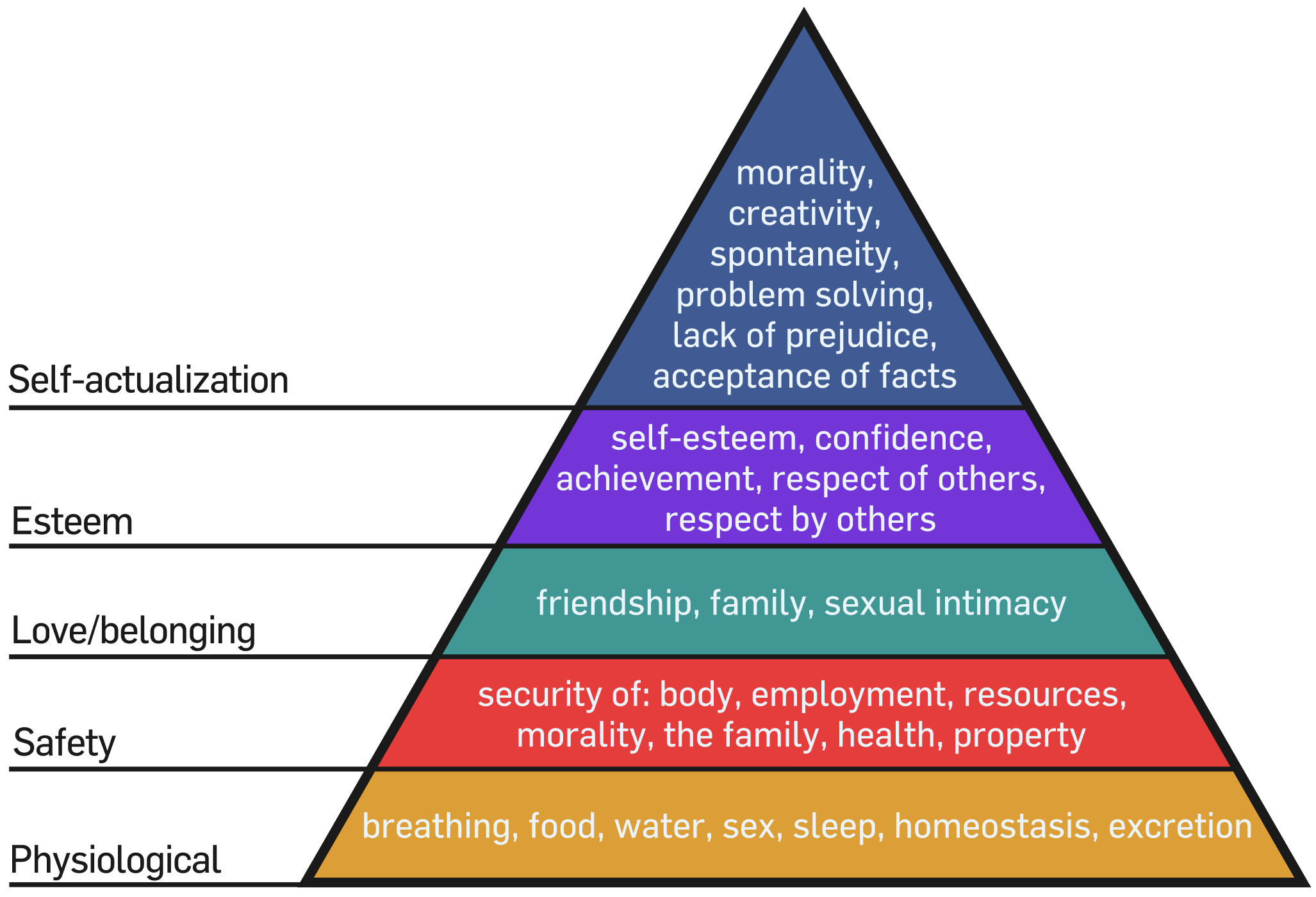

It’s how our brain generally works to assess a situation quickly to decide whether where we are, and who we are with, are safe. It is our most basic instinct. It gives us a sense of safety and security—one of our most basic needs in Maslow's hierarchy.

Difference feels suspect to us until we discover what is similar or familiar to our own experience. It feels natural to make snap judgments about people and situations that are not familiar to us. That said, it can be surprising that we have such a hard time accepting that everyone has biases.

Acknowledging our biases is hard, for many of us. It seems many have come to believe that having a bias means we are automatically hateful, racist, insensitive, or sexist people. It’s no wonder we get defensive when our biases are brought to our attention. It feels like we are being accused, side-swiped by a Mack truck.

Yet, advanced research on the brain shows that we are hardwired for survival. We make automatic assumptions based on our personal history, our DNA, and family and cultural values and beliefs that have been passed on. These are our attempts to feel safe and secure.

My Personal Exploration

As a systemic psychotherapist, I have had to learn to tease out and identify my own personal biases. Most of these biases were not so much about ethnicity and race. They were about how I thought people “should” feel, what I thought they “should“ believe, and how I expected them to behave.

This was an uncomfortable process of discovery…

From my experience growing up in a working class neighborhood, I had “learned“ to be suspect of rich people, even though success was often measured by what kind of house one lived in.

From my religious upbringing, I had “learned“ to be suspect of atheists, and that only “believers” go to heaven.

From my educational privilege, I had “learned“ that someone with a college degree was “smarter” than someone who worked with their hands.

From my Italian-American background, I had “learned “that girls don’t leave home before marriage, and even then, they were expected to be at the family home for Sunday dinner at 2 pm every week.

I had “learned “ to judge people based on behavior and choices. I had “learned“ that some people were worthy of respect, and some weren’t. I had “learned” gender roles, expectations, values, and beliefs, mostly without any lectures or specific training; I learned most of it by observation.

And these were just the most obvious. There were many other judgments about others: Couples who didn’t want children; people who didn’t go to church; tall people; overweight people; confident people; women who weren’t afraid to speak their mind, especially in anger; people who didn’t like the beach…

Once my eyes were opened to the truth of my prejudgments, my list of biases seemed endless.

Uncovering and Acknowledging My Biases

Gratefully, life has forced me to come face-to-face with people and situations that have provided me with new perspectives. They nudged me to excavate my deeply held, often unconscious beliefs, in favor of more honest examination. The process hasn’t always been easy; sometimes it was downright frightening and uncomfortable.

But, I am eternally grateful for each of these humbling experiences. They have helped me throw away the rigid boxes I tended to place people in—those who were outside my own tribe. Each has helped me let go of yet another barrier that had kept me from connecting with myself, God and others.

By accepting that I am the product of my environment, I can now look at my implicit biases with more self-acceptance. From this, I have learned self-compassion, even while acknowledging my weaknesses with “soft eyes.” In turn, I have become able to extend the same compassion to others, especially those who were seemingly different from me.

This has moved me closer to the more expansive realization: that we are all made of the same spirit and matter. More importantly, my eyes have opened to how connected we really are. We may appear to be separate people living our lives independent of others, but each of our lives is but a partial expression of something so much bigger than the “me” housed inside our individual bodies.

Connecting in the Field

As I have written before, my work as a therapist has helped me in innumerable ways. It has helped me to understand, from the inside out, what this mysterious connection is. When I sit with a client and am really present, I let go of “ideas of wrongdoing and right-doing,” as the poet Rumi describes—the place of non-judgment,

I sometimes lose the sense of time and place, of me and the “other.” I can feel into their experience. I don’t know it is happening until after the moment has passed, and I sense that something bigger than either of us just happened.

I know what I know to be true about my client, though I can’t always explain how; it feels more intuitive than rational. I experience it as an opening to another dimension, a connection to the Spirit within and between us, a bridge between one heart and another. When this happens, the space that exists between us fades.

When I share this phenomenon with more seasoned colleagues and friends, I receive mostly affirming nods. When I was first starting out as a social worker, I had thought that my job was to “fix”those who I worked with. The stress of believing that I should know what they needed and how to get that for them was overwhelming. I nearly left the helping field for fear of failing those most in need.

What I realized over many years, though it was not spelled out specifically, is that the most profound gift I could give those who sought help was to listen to the yearnings of their heart with my own open heart. Learning to just be “present” and fully attentive to who the person was—what they were saying and how they were saying it—was my first important lesson.

This heart-to-heart is what energizes me to stay in the field.

I agree with the sentiments of many of my clients: that there are so few places outside the therapy office where they experience this sense of oneness. Our culture tends to separate people into categories. We judge others based on how they look, what they believe, and who they love.

Sometimes the pull is so strong and so subtle, we don’t even notice that we are being conditioned. But in the therapy office, at least some of the time, we access a field that reminds us that we are not so separate as we think. We really are one in a field of energy called Love.

“Out beyond idea of wrongdoing and right-doing,

there is a field. I will meet you there.

When the soul lies down in that grass

the world is too full to talk about

Ideas, language, even the phrase ‘each other’

doesn’t make any sense.”

Coming up, I’ll describe how this internal shift has opened me to the field Rumi describes. I’ll share some of the ways I am reminded that there is field that is so much richer and more vibrant than the small world we think we are creating on our own.

When have you felt drawn to people who you didn’t even know?

Have you ever felt your heart expand beyond the boundaries of your body?

When has your heart opened to something you couldn’t even name, but felt sure about?

Share your comments at the bottom of the page.

© Whatismyhealth

Understanding our attachment styles can help us bypass destructive strategies and find a more authentic connection.